Intermittent Fasting (IF), also known as intermittent energy restriction or mimics fasting diets involves alternating periods of normal energy intake and energy restriction (or complete fasting). It mainly includes alternate-day fasting, periodic fasting, time-restricted feeding, and Ramadan fasting.

Numerous clinical studies have confirmed varying degrees of benefits of intermittent fasting for obesity, metabolic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and even cancer. So, what are the clinical applications and future directions of this approach? Recently, Dr. Zhang Zhikai, Deputy Chief Physician of the Nutrition Department at Guangzhou Fuda Cancer Hospital, shared insights on intermittent fating.

01 Models of Intermittent Fasting

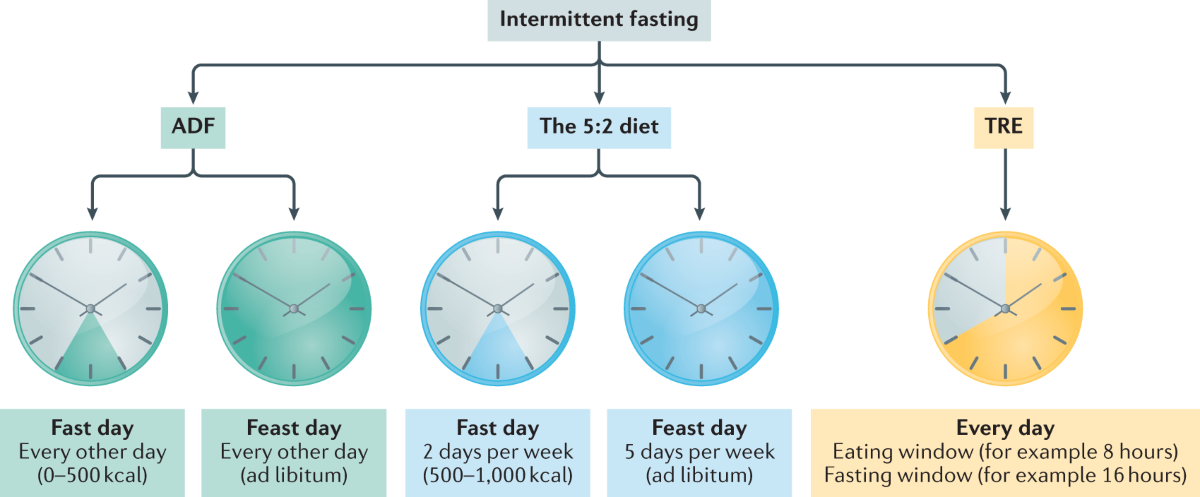

Intermittent fasting can be simply defined as alternating fasting and feeding periods. The most studied intermittent fasting models include:

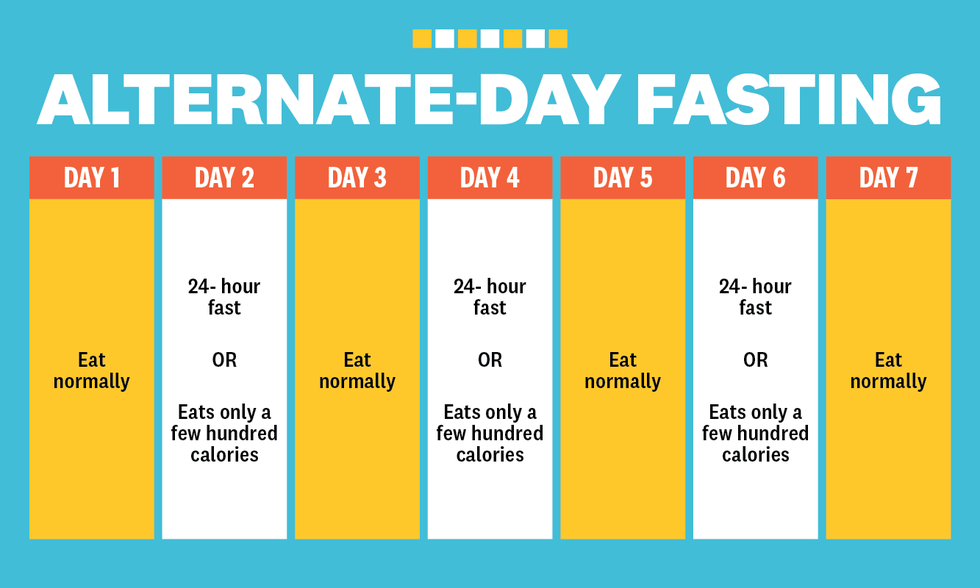

(1) Alternate-Day Fasting (ADF): Eating normally on days 1, 3, 5, and 7, and fasting completely (drinking water or meal replacements allowed) on days 2, 4, 6, and 8. Fasting days (0~500 kcal) alternate with feeding days (unrestricted intake).

(2) 5:2 Fasting: Fasting for two days a week, with unrestricted intake on the remaining five days.

(3) Time-Restricted Feeding: Narrowing the eating window to 6-8 hours daily, with eating only during designated times.

Fasting-Mimicking Diet (FMD) is a variant of intermittent fasting, characterized by a low-protein, low-calorie diet with high unsaturated fats and micronutrients, providing 10%-50% of normal calorie intake. It can last for 2-5 days and can alternate with a standard diet. FMD can be tailored based on individual health conditions and goals to ensure safety and sustainability.

Caloric Restriction (CR) refers to limiting daily calorie intake while providing adequate nutrients to prevent malnutrition, also known as Dietary Restriction (DR).

Compared to intermittent fasting, caloric restriction targets fat storage by maintaining a consistently lower energy intake throughout the day, preventing excessive energy from being stored as fat. This approach requires strict daily energy intake control, whereas intermittent fasting requires only restricting energy intake during specified fasting periods, allowing free eating during the rest of the time.

02 Roles of Intermittent Fasting

For Weight Management

A study by Heilbronn et al. on 16 normal-weight subjects found that just 22 days of intermittent fasting reduced body weight by approximately 2%~3%. Similar weight loss effects were observed in overweight/obese subjects. Varady's meta-analysis on intermittent fasting/caloric restriction effects on overweight/obese patients showed a weight reduction of about 6%~8% after 8-12 weeks of intermittent fasting.

Further research revealed that when weight loss is achieved through caloric restriction, 75% of the weight loss comes from reduced fat content and 25% from lean body mass reduction. In contrast, with intermittent fasting, 90% of the weight loss comes from reduced fat content and 10% from lean body mass reduction.

For Metabolic Diseases

Intermittent fasting can promote metabolism and improve energy utilization efficiency. Halberg et al. found that after a 2-week intermittent fasting intervention in 8 healthy male subjects, although fasting insulin and fasting glucose levels did not change significantly, insulin sensitivity increased significantly. A normal glucose-high insulin clamp test showed that after 14 days of intermittent fasting, the rate of glucose uptake increased by 15.9%. Moreover, Seimon's meta-analysis of clinical trials on intermittent fasting/caloric restriction published before November 2014 found that intermittent fasting increases insulin sensitivity and improves glucose homeostasis similarly to caloric restriction.

For Cardiovascular Diseases

Some studies suggest that intermittent fasting can improve risk factors for cardiovascular metabolic diseases, such as blood pressure, LDL cholesterol levels, triglyceride levels, glycated hemoglobin levels, and insulin resistance, and reduce the risk of atherosclerosis.

For Cancer

Currently, there are no large-scale prospective studies specifically reporting the effects of intermittent fasting on humans. However, since fasting can affect weight and metabolism, and weight reduction and metabolic improvements are beneficial for cancer prevention, some speculate that intermittent fasting may be beneficial for cancer prevention.

Animal studies have found that fasting for a certain period can reduce certain cancer risk factors, including lowering fasting blood sugar, insulin, leptin levels, and increasing adiponectin levels, all of which have been shown to be related to cancer mechanisms:

o IGF-1: High levels of IGF-1 are associated with breast cancer, colon cancer, and prostate cancer, while intermittent fasting can lower IGF-1 levels, reducing stimulation of cancer cell growth.

o Ketones: Ketones may slow tumor growth and prevent oxidative stress. Under fasting conditions, the liver produces ketones from fatty acids, serving as the main energy source for the brain.

o Autophagy: Fasting in mammals has been shown to induce autophagy, a starvation-induced autophagy that can protect normal cells from malignant transformation. Additionally, autophagy has been shown to make cancer cells more sensitive to chemotherapy.

Several small-scale preliminary clinical studies have shown that fasting before and during chemotherapy (significantly reducing calorie and/or protein intake) may reduce acute and chronic adverse effects of chemotherapy and improve quality of life.

In addition, in 2020, Italian scholars published a study titled "Fasting-mimicking diet and hormone therapy induce breast cancer regression" in Nature, finding that periodic use of a fasting-mimicking diet (FMD) can enhance the effectiveness of endocrine therapy and serve as an adjunct to endocrine therapy for breast cancer.

In 2021, researchers from the University of Milan, Italy, published a research paper in the top academic journal Cancer Discovery, confirming that short-term fasting is safe and can enhance anti-tumor immunity.

Currently, there are no established guidelines for intermittent fasting tailored for cancer patients domestically or internationally. It should be noted that although many trials have found fasting to be safe and tolerable for cancer patients, potential risks exist, such as exacerbating malnutrition in cancer patients, delaying wound healing, reducing immune function, and increasing infection risk.

Overall, although research on intermittent fasting remains controversial with uncertain overall benefits and difficult-to-control risks, exploring and studying the therapeutic effects of IF still holds certain value, especially when combined with healthy eating patterns and regular physical activity, which may be related to unknown cancer mechanisms.