Breast cancer is a type of cancer originating from breast tissue, most commonly from the inner lining of milk ducts or the lobules that supply the ducts with milk.Cancers originating from ducts are known as ductal carcinomas, while those originating from lobules are known as lobular carcinomas. Breast cancer occurs in humans and other mammals. While the overwhelming majority of human cases occur in women, male breast cancer can also occur.

The benefit versus harms of breast cancer screening is controversial. The characteristics of the cancer determine the treatment, which may include surgery, medications (hormonal therapy and chemotherapy), radiation and/or immunotherapy.Surgery provides the single largest benefit, and to increase the likelihood of cure, several chemotherapy regimens are commonly given in addition. Radiation is used after breast-conserving surgery and substantially improves local relapse rates and in many circumstances also overall survival.

Worldwide, breast cancer accounts for 22.9% of all cancers (excluding non-melanoma skin cancers) in women.[5] In 2008, breast cancer caused 458,503 deaths worldwide (13.7% of cancer deaths in women). Breast cancer is more than 100 times more common in women than in men, although men tend to have poorer outcomes due to delays in diagnosis.

Prognosis and survival rates for breast cancer vary greatly depending on the cancer type, stage, treatment, and geographical location of the patient. Survival rates in the Western world are high;[6] for example, more than 8 out of 10 women (84%) in England diagnosed with breast cancer survive for at least 5 years.In developing countries, however, survival rates are much poorer.

Signs and symptoms

The first noticeable symptom of breast cancer is typically a lump that feels different from the rest of the breast tissue. More than 80% of breast cancer cases are discovered when the woman feels a lump. The earliest breast cancers are detected by a mammogram. Lumps found in lymph nodes located in the armpits can also indicate breast cancer.

Indications of breast cancer other than a lump may include thickening different from the other breast tissue, one breast becoming larger or lower, a nipple changing position or shape or becoming inverted, skin puckering or dimpling, a rash on or around a nipple, discharge from nipple/s, constant pain in part of the breast or armpit, and swelling beneath the armpit or around the collarbone. Pain ("mastodynia") is an unreliable tool in determining the presence or absence of breast cancer, but may be indicative of other breast health issues.

Inflammatory breast cancer is a particular type of breast cancer which can pose a substantial diagnostic challenge. Symptoms may resemble a breast inflammation and may include itching, pain, swelling, nipple inversion, warmth and redness throughout the breast, as well as an orange-peel texture to the skin referred to as peau d'orange;[9] the absence of a discernible lump may delay detection dangerously.

Another reported symptom complex of breast cancer is Paget's disease of the breast. This syndrome presents as skin changes resembling eczema, such as redness, discoloration, or mild flaking of the nipple skin. As Paget's disease of the breast advances, symptoms may include tingling, itching, increased sensitivity, burning, and pain. There may also be discharge from the nipple. Approximately half of women diagnosed with Paget's disease of the breast also have a lump in the breast.

In rare cases, what initially appears as a fibroadenoma (hard, movable non-cancerous lump) could in fact be a phyllodes tumor. Phyllodes tumors are formed within the stroma (connective tissue) of the breast and contain glandular as well as stromal tissue. Phyllodes tumors are not staged in the usual sense; they are classified on the basis of their appearance under the microscope as benign, borderline, or malignant.

Occasionally, breast cancer presents as metastatic disease—that is, cancer that has spread beyond the original organ. The symptoms caused by metastatic breast cancer will depend on the location of metastasis. Common sites of metastasis include bone, liver, lung and brain.

Unexplained weight loss can occasionally herald an occult breast cancer, as can symptoms of fevers or chills. Bone or joint pains can sometimes be manifestations of metastatic breast cancer, as can jaundice or neurological symptoms. These symptoms are called non-specific, meaning they could be manifestations of many other illnesses.

Most symptoms of breast disorders, including most lumps, do not turn out to represent underlying breast cancer. Fewer than 20% of lumps, for example, are cancerous,and benign breast diseases such as mastitis and fibroadenoma of the breast are more common causes of breast disorder symptoms. Nevertheless, the appearance of a new symptom should be taken seriously by both patients and their doctors, because of the possibility of an underlying breast cancer at almost any age.

Risk factors

Main article: Risk factors of breast cancer

The primary risk factors for breast cancer are female sex and older age.Other potential risk factors include: lack of childbearing or lack of breastfeeding, higher levels of certain hormones,certain dietary patterns, and obesity.

Lifestyle

See also: List of breast carcinogenic substances

Smoking tobacco appears to increase the risk of breast cancer, with the greater the amount smoked and the earlier in life that smoking began, the higher the risk. In those who are long-term smokers, the risk is increased 35% to 50%. A lack of physical activity has been linked to ~10% of cases.

The association between breast feeding and breast cancer has not been clearly determined; some studies have found support for an association while others have not. In the 1980s, the abortion–breast cancer hypothesis posited that induced abortion increased the risk of developing breast cancer. This hypothesis was the subject of extensive scientific inquiry, which concluded that neither miscarriages nor abortions are associated with a heightened risk for breast cancer.There may be an association between use of oral contraceptives and the development of premenopausal breast cancer, but whether oral contraceptives use may actually cause premenopausal breast cancer is a matter of debate. If there is indeed a link, the absolute effect is small.In those with mutations in the breast cancer susceptibility genes BRCA1 or BRCA2, or who have a family history of breast cancer, use of modern oral contraceptives does not appear to affect the subsequent[clarification needed (subsequent to what?)] risk of breast cancer.

There is a relationship between diet and breast cancer, including an increased risk with a high fat diet,alcohol intake, and obesity. Dietary iodine deficiency may also play a role.

Other risk factors include radiation,and shift-work.A number of chemicals have also been linked including: polychlorinated biphenyls, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, organic solvents and a number of pesticides.Although the radiation from mammography is a low dose, it is estimated that yearly screening from 40 to 80 years of age will cause approximately 225 cases of fatal breast cancer per million women screened.

Genetics

Some genetic susceptibility may play a minor role in most cases.Overall, however, genetics is believed to be the primary cause of 5–10% of all cases. In those with zero, one or two affected relatives, the risk of breast cancer before the age of 80 is 7.8%, 13.3%, and 21.1% with a subsequent mortality from the disease of 2.3%, 4.2%, and 7.6% respectively.In those with a first degree relative with the disease the risk of breast cancer between the age of 40 and 50 is double that of the general population.

In less than 5% of cases, genetics plays a more significant role by causing a hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome.This includes those who carry the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation.These mutations account for up to 90% of the total genetic influence with a risk of breast cancer of 60–80% in those affected.Other significant mutations include: p53 (Li–Fraumeni syndrome), PTEN (Cowden syndrome), and STK11 (Peutz–Jeghers syndrome), CHEK2, ATM, BRIP1, and PALB2. In 2012, researchers said that there are four genetically distinct types of the breast cancer and that in each type, hallmark genetic changes lead to many cancers.

Medical conditions

Certain breast changes: atypical hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ found in benign breast conditions such as fibrocystic breast changes are correlated with an increased breast cancer risk.

Pathophysiology

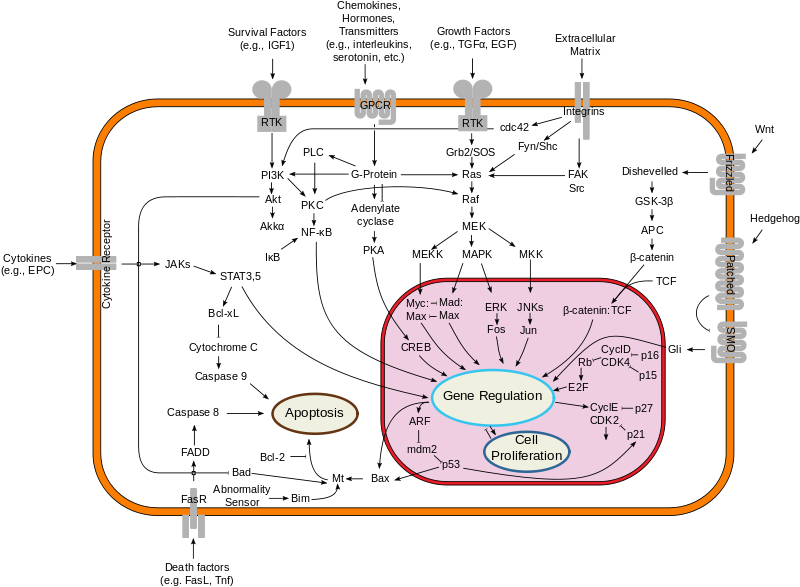

Breast cancer, like other cancers, occurs because of an interaction between an environmental (external) factor and a genetically susceptible host. Normal cells divide as many times as needed and stop. They attach to other cells and stay in place in tissues. Cells become cancerous when they lose their ability to stop dividing, to attach to other cells, to stay where they belong, and to die at the proper time.

Normal cells will commit cell suicide (apoptosis) when they are no longer needed. Until then, they are protected from cell suicide by several protein clusters and pathways. One of the protective pathways is the PI3K/AKT pathway; another is the RAS/MEK/ERK pathway. Sometimes the genes along these protective pathways are mutated in a way that turns them permanently "on", rendering the cell incapable of committing suicide when it is no longer needed. This is one of the steps that causes cancer in combination with other mutations. Normally, the PTEN protein turns off the PI3K/AKT pathway when the cell is ready for cell suicide. In some breast cancers, the gene for the PTEN protein is mutated, so the PI3K/AKT pathway is stuck in the "on" position, and the cancer cell does not commit suicide.

Mutations that can lead to breast cancer have been experimentally linked to estrogen exposure.

Failure of immune surveillance, the removal of malignant cells throughout one's life by the immune system. Abnormal growth factor signaling in the interaction between stromal cells and epithelial cells can facilitate malignant cell growth.[50][51] In breast adipose tissue, overexpression of leptin leads to increased cell proliferation and cancer.

In the United States, 10 to 20 percent of patients with breast cancer and patients with ovarian cancer have a first- or second-degree relative with one of these diseases. The familial tendency to develop these cancers is called hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome. The best known of these, the BRCA mutations, confer a lifetime risk of breast cancer of between 60 and 85 percent and a lifetime risk of ovarian cancer of between 15 and 40 percent. Some mutations associated with cancer, such as p53, BRCA1 and BRCA2, occur in mechanisms to correct errors in DNA. These mutations are either inherited or acquired after birth. Presumably, they allow further mutations, which allow uncontrolled division, lack of attachment, and metastasis to distant organs.However there is strong evidence of residual risk variation that goes well beyond hereditary BRCA gene mutations between carrier families. This is caused by unobserved risk factors. This implicates environmental and other causes as triggers for breast cancers. The inherited mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes can interfere with repair of DNA cross links and DNA double strand breaks (known functions of the encoded protein) These carcinogens cause DNA damage such as DNA cross links and double strand breaks that often require repairs by pathways containing BRCA1 and BRCA2.However, mutations in BRCA genes account for only 2 to 3 percent of all breast cancers.Levin et al. say that cancer may not be inevitable for all carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.About half of hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndromes involve unknown genes.

Diagnosis

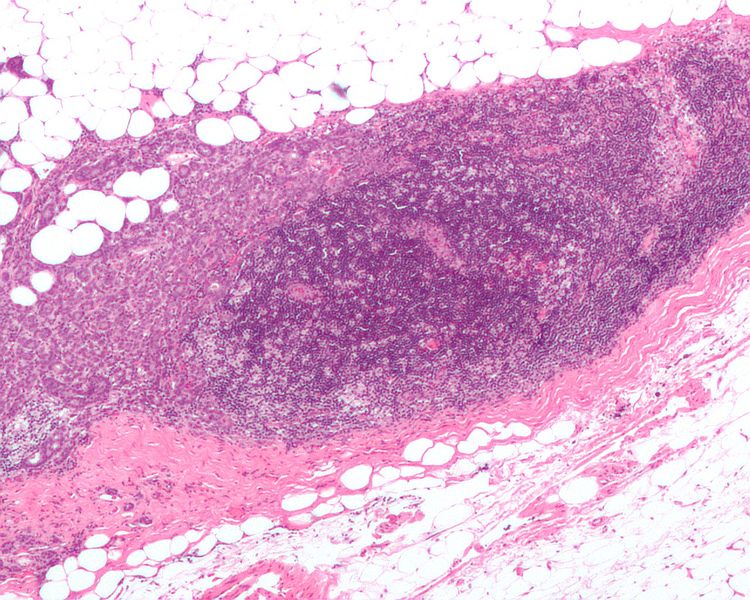

Most types of breast cancer are easy to diagnose by microscopic analysis of a sample—or biopsy—of the affected area of the breast. There are, however, rarer types of breast cancer that require specialized lab exams.

The two most commonly used screening methods, physical examination of the breasts by a healthcare provider and mammography, can offer an approximate likelihood that a lump is cancer, and may also detect some other lesions, such as a simple cyst.[60] When these examinations are inconclusive, a healthcare provider can remove a sample of the fluid in the lump for microscopic analysis (a procedure known as fine needle aspiration, or fine needle aspiration and cytology—FNAC) to help establish the diagnosis. The needle aspiration may be performed in a healthcare provider's office or clinic using local anaesthetic if required.[clarification needed] A finding of clear fluid makes the lump highly unlikely to be cancerous, but bloody fluid may be sent off for inspection under a microscope for cancerous cells. Together, physical examination of the breasts, mammography, and FNAC can be used to diagnose breast cancer with a good degree of accuracy.

Other options for biopsy include a core biopsy or vacuum-assisted breast biopsy, which are procedures in which a section of the breast lump is removed; or an excisional biopsy, in which the entire lump is removed. Very often the results of physical examination by a healthcare provider, mammography, and additional tests that may be performed in special circumstances (such as imaging by ultrasound or MRI) are sufficient to warrant excisional biopsy as the definitive diagnostic and primary treatment method.

Classification

Main article: Breast cancer classification

Breast cancers are classified by several grading systems. Each of these influences the prognosis and can affect treatment response. Description of a breast cancer optimally includes all of these factors.

Histopathology. Breast cancer is usually classified primarily by its histological appearance. Most breast cancers are derived from the epithelium lining the ducts or lobules, and these cancers are classified as ductal or lobular carcinoma. Carcinoma in situ is growth of low grade cancerous or precancerous cells within a particular tissue compartment such as the mammary duct without invasion of the surrounding tissue. In contrast, invasive carcinoma does not confine itself to the initial tissue compartment.

Grade. Grading compares the appearance of the breast cancer cells to the appearance of normal breast tissue. Normal cells in an organ like the breast become differentiated, meaning that they take on specific shapes and forms that reflect their function as part of that organ. Cancerous cells lose that differentiation. In cancer, the cells that would normally line up in an orderly way to make up the milk ducts become disorganized. Cell division becomes uncontrolled. Cell nuclei become less uniform. Pathologists describe cells as well differentiated (low grade), moderately differentiated (intermediate grade), and poorly differentiated (high grade) as the cells progressively lose the features seen in normal breast cells. Poorly differentiated cancers (the ones whose tissue is least like normal breast tissue) have a worse prognosis.

Stage. Breast cancer staging using the TNM system is based on the size of the tumor (T), whether or not the tumor has spread to the lymph nodes (N) in the armpits, and whether the tumor has metastasized (M) (i.e. spread to a more distant part of the body). Larger size, nodal spread, and metastasis have a larger stage number and a worse prognosis.

The main stages are:

Stage 0 is a pre-cancerous or marker condition, either ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS).

Stages 1–3 are within the breast or regional lymph nodes.

Stage 4 is 'metastatic' cancer that has a less favorable prognosis.

Receptor status. Breast cancer cells have receptors on their surface and in their cytoplasm and nucleus. Chemical messengers such as hormones bind to receptors, and this causes changes in the cell. Breast cancer cells may or may not have three important receptors: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2.

ER+ cancer cells depend on estrogen for their growth, so they can be treated with drugs to block estrogen effects (e.g. tamoxifen), and generally have a better prognosis. HER2+ breast cancer had a worse prognosis, but HER2+ cancer cells respond to drugs such as the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab (in combination with conventional chemotherapy), and this has improved the prognosis significantly.Cells with none of these receptors are called triple-negative although they frequently express receptors for other hormones such as androgen receptor and prolactin receptor.

In cases of breast cancer with low risk for metastasis, the risks associated with PET scans, CT scans, or bone scans outweigh the possible benefits.This is because these procedures expose the patient to a substantial amount of potentially dangerous ionizing radiation.

DNA assays. DNA testing of various types including DNA microarrays have compared normal cells to breast cancer cells. The specific changes in a particular breast cancer can be used to classify the cancer in several ways, and may assist in choosing the most effective treatment for that DNA type.

Prevention

Women may reduce their risk of breast cancer by maintaining a healthy weight, drinking less alcohol, being physically active and breastfeeding their children. These modifications might prevent 38% of breast cancers in the US, 42% in the UK, 28% in Brazil and 20% in China. The benefits with moderate exercise such as brisk walking are seen at all age groups including postmenopausal women.Marine omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids appear to reduce the risk.

Removal of both breasts before any cancer has been diagnosed or any suspicious lump or other lesion has appeared (a procedure known as prophylactice bilateral mastectomy) may be considered in people with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, which are associated with a substantially heightened risk for an eventual diagnosis of breast cancer.

The selective estrogen receptor modulators (such as tamoxifen) reduce the risk of breast cancer but increase the risk of thromboembolism and endometrial cancer. There is no overall change in the risk of death.The benefit of breast cancer reduction continues for at least five years after stopping a course of treatment with these medications.

Screening

Main article: Breast cancer screening

Breast cancer screening refers to testing otherwise-healthy women for breast cancer in an attempt to achieve an earlier diagnosis under the assumption that early detection will improve outcomes. A number of screening test have been employed including: clinical and self breast exams, mammography, genetic screening, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging.

A clinical or self breast exam involves feeling the breast for lumps or other abnormalities. Clinical breast exams are performed by health care providers, while self breast exams are performed by the person themselves.Evidence dose not support the effectiveness of either type of breast exam, as by the time a lump is large enough to be found it is likely to have been growing for several years and thus soon be large enough to be found without an exam.Mammographic screening for breast cancer uses X-rays to examine the breast for any uncharacteristic masses or lumps. During a screening, the breast is compressed and a technician takes photos from multiple angles. A general mammogram takes photos of the entire breast, while a diagnostic mammogram focuses on a specific lump or area of concern.

A number of national bodies continue to recommend breast cancer screening. For the average woman, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends mammography every two years in women between the ages of 50 and 74, the Council of Europe recommends mammography between 50 and 69 with most programs using a 2 year frequency,and in Canada screening is recommended between the ages of 50 and 74 at a frequency of 2 to 3 years. These task force reports point out that in addition to unnecessary surgery and anxiety, the risks of more frequent mammograms include a small but significant increase in breast cancer induced by radiation. Whether MRI as a screening method has greater harms or benefits when compared to standard mammography is not known.

The Cochrane Collaboration (2011) states that the best quality evidence neither demonstrates a reduction in either cancer specific, nor a reduction in all cause mortality from screening mammography. When less rigorous trials are added to the analysis there is a reduction in breast cancer specific mortality of 0.05% (a relative decrease of 15%).Screening results in a 30% increase in rates of over-diagnosis and over-treatment, resulting in the view that it is not clear whether mammography screening does more good or harm. Cochrane states that, due to recent improvements in breast cancer treatment, and the risks of false positives from breast cancer screening leading to unnecessary treatment, "it therefore no longer seems reasonable to attend for breast cancer screening" at any age.