Stomach cancer, or gastric cancer, refers to cancer arising from any part of the stomach. Stomach cancer causes about 800,000 deaths worldwide per year.Prognosis is poor (5-year survival <5 to 15%) because most patients present with advanced disease.

Signs and symptoms

Stomach cancer is often either asymptomatic (producing no noticeable symptoms) or it may cause only nonspecific symptoms (symptoms which are not specific to just stomach cancer, but also to other related or unrelated disorders) in its early stages. By the time symptoms occur, the cancer has often reached an advanced stage (see below) and may have also metastasized (spread to other, perhaps distant, parts of the body), which is one of the main reasons for its relatively poor prognosis.[citation needed] Stomach cancer can cause the following signs and symptoms:

Stage 1 (Early)

—Indigestion or a burning sensation (heartburn)

—Loss of appetite, especially for meat

—Abdominal discomfort or irritation

Stage 2 (Middle)

—Weakness and fatigue

—Bloating of the stomach, usually after meals

Stage 3 (Late)

—Abdominal pain in the upper abdomen

—Nausea and occasional vomiting

—Diarrhea or constipation

—Weight loss

—Bleeding (vomiting blood or having blood in the stool) which will appear as black. This can lead to anemia.

—Dysphagia; this feature suggests a tumor in the cardia or extension of the gastric tumor into the esophagus.

Note that these can be symptoms of other problems such as a stomach virus, gastric ulcer or tropical sprue.

Causes

Most stomach cancer is caused by Helicobacter pylori infection. Dietary factors are not proven causes, but some foods, such as smoked foods, salted fish and meat, and pickled vegetables are associated with a higher risk. Nitrates and nitrites in cured meats can be converted by certain bacteria, including H. pylori, into compounds that have been found to cause stomach cancer in animals. On the other hand, the American Cancer Society recommends eating fresh fruits and vegetables that contain antioxidant vitamins, such as A and C, and says that they lower the risk of stomach cancer, and a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower rates of stomach cancer.

Smoking increases the risk of developing gastric cancer significantly, from 40% increased risk for current smokers to 82% increase for heavy smokers. Gastric cancers due to smoking mostly occur in the upper part of the stomach near theesophagus[3][5][6] Some studies show increased risk with alcohol consumption as well.

Other factors associated with increased risk are autoimmune atrophic gastritis, pernicious anemia, Menetrier's disease (hyperplastic, hypersecretory gastropathy), intestinal metaplasia, and genetic factors.

H. pylori is the main risk factor in 65–80% of gastric cancers, but in only 2% of such infections. The mechanism by which H. pylori induces stomach cancer potentially involves chronic inflammation, or the action of H. pylori virulence factors such as CagA. Approximately ten percent of cases show a genetic component. Some studies indicate that bracken consumption and spores are correlated with incidence of stomach cancer, though causality has yet to be established.

Gastric cancer shows a male predominance in its incidence as up to three males are affected for every female. Estrogen may protect women against the development of this cancer form. A very small percentage of diffuse-type gastric cancers (see Histopathology below) are thought to be genetic. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) has recently been identified and research is ongoing. However, genetic testing and treatment options are already available for families at risk.

The International Cancer Genome Consortium is leading efforts to map stomach cancer's complete genome.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

To find the cause of symptoms, the doctor asks about the patient's medical history, does a physical exam, and may order laboratory studies. The patient may also have one or all of the following exams:

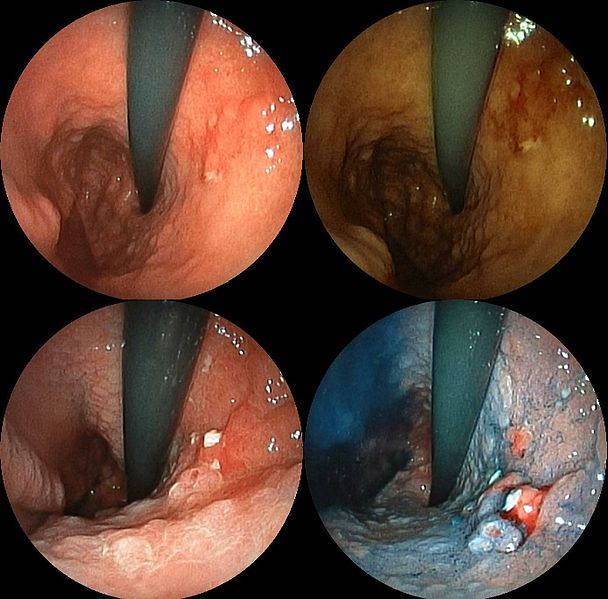

—Gastroscopic exam is the diagnostic method of choice. This involves insertion of a fiber optic camera into the stomach to visualize it.

—Upper GI series (may be called barium roentgenogram)

—Computed tomography or CT scanning of the abdomen may reveal gastric cancer, but is more useful to determine invasion into adjacent tissues, or the presence of spread to local lymph nodes.

Abnormal tissue seen in a gastroscope examination will be biopsied by the surgeon or gastroenterologist. This tissue is then sent to a pathologist for histological examination under a microscope to check for the presence of cancerous cells. A biopsy, with subsequent histological analysis, is the only sure way to confirm the presence of cancer cells.

Various gastroscopic modalities have been developed to increase yield of detected mucosa with a dye that accentuates the cell structure and can identify areas of dysplasia. Endocytoscopy involves ultra-high magnification to visualize cellular structure to better determine areas of dysplasia. Other gastroscopic modalities such as optical coherence tomography are also being tested investigationally for similar applications.

A number of cutaneous conditions are associated with gastric cancer. A condition of darkened hyperplasia of the skin, frequently of the axilla and groin, known as acanthosis nigricans, is associated with intra-abdominal cancers such as gastric cancer. Other cutaneous manifestations of gastric cancer include tripe palms (a similar darkening hyperplasia of the skin of the palms) and the Leser-Trelat sign, which is the rapid development of skin lesions known as seborrheic keratoses.

Various blood tests may be done, including: Complete Blood Count (CBC) to check for anemia. Also, a stool test may be performed to check for blood in the stool.

Histopathology

Gastric adenocarcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor, originating from glandular epithelium of the gastric mucosa. Stomach cancers are overwhelmingly adenocarcinomas (90%). Histologically, there are two major types of gastric adenocarcinoma (Lauren classification): intestinal type or diffuse type. Adenocarcinomas tend to aggressively invade the gastric wall, infiltrating the muscularis mucosae, the submucosa, and thence the muscularis propria. Intestinal type adenocarcinoma tumor cells describe irregular tubular structures, harboring pluristratification, multiple lumens, reduced stroma ("back to back" aspect). Often, it associates intestinal metaplasia in neighboring mucosa. Depending on glandular architecture, cellular pleomorphism and mucosecretion, adenocarcinoma may present 3 degrees of differentiation: well, moderate and poorly differentiated. Diffuse type adenocarcinoma (mucinous, colloid, linitis plastica, leather-bottle stomach) Tumor cells are discohesive and secrete mucus which is delivered in the interstitium, producing large pools of mucus/colloid (optically "empty" spaces). It is poorly differentiated. If the mucus remains inside the tumor cell, it pushes the nucleus to the periphery: "signet-ring cell".

Around 5% of gastric malignancies are lymphomas (MALTomas, or MALT lymphoma).

Carcinoid and stromal tumors may also occur.

Staging

If cancer cells are found in the tissue sample, the next step is to stage, or find out the extent of the disease. Various tests determine whether the cancer has spread and, if so, what parts of the body are affected. Because stomach cancer can spread to the liver, the pancreas, and other organs near the stomach as well as to the lungs, the doctor may order a CT scan, a PET scan, an endoscopic ultrasound exam, or other tests to check these areas. Blood tests for tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) may be ordered, as their levels correlate to extent of metastasis, especially to the liver, and the cure rate.

Staging may not be complete until after surgery. The surgeon removes nearby lymph nodes and possibly samples of tissue from other areas in the abdomen for examination by a pathologist.

The clinical stages of stomach cancer are:

—Stage 0. Limited to the inner lining of the stomach. Treatable by endoscopic mucosal resection when found very early (in routine screenings); otherwise by gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy without need for chemotherapy or radiation.

—Stage I. Penetration to the second or third layers of the stomach (Stage 1A) or to the second layer and nearby lymph nodes (Stage 1B). Stage 1A is treated by surgery, including removal of the omentum. Stage 1B may be treated with chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil) and radiation therapy.

—Stage II. Penetration to the second layer and more distant lymph nodes, or the third layer and only nearby lymph nodes, or all four layers but not the lymph nodes. Treated as for Stage I, sometimes with additional neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

—Stage III. Penetration to the third layer and more distant lymph nodes, or penetration to the fourth layer and either nearby tissues or nearby or more distant lymph nodes. Treated as for Stage II; a cure is still possible in some cases.

—Stage IV. Cancer has spread to nearby tissues and more distant lymph nodes, or has metastatized to other organs. A cure is very rarely possible at this stage. Some other techniques to prolong life or improve symptoms are used, including laser treatment, surgery, and/or stents to keep the digestive tract open, and chemotherapy by drugs such as 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, epirubicin, etoposide, docetaxel, oxaliplatin, capecitabine, or irinotecan.

The TNM staging system is also used.

In a study of open-access endoscopy in Scotland, patients were diagnosed 7% in Stage I 17% in Stage II, and 28% in Stage III. A Minnesota population was diagnosed 10% in Stage I, 13% in Stage II, and 18% in Stage III. However in a high-risk population in the Valdivia Province of southern Chile, only 5% of patients were diagnosed in the first two stages and 10% in stage III.